“Lofty” was in his early 40s in Beechworth Jail when he realised he had wasted his life so far and was determined that when his parole came up he would go straight. It was in the mid-1960s.

In those days prisoners were not permitted to serve their parole in Beechworth. My father, a parole officer and Anglican chaplain of the jail, pleaded Lofty’s case, arguing that the sewerage project had started as was in desperate need of labourers. Lofty was a big, strong, fit man. He would be ideal. And to send him back to Melbourne would make a relapse more likely.

He stayed in Beechworth gainfully employed on the sewerage project.

I recall one day we had to move the heavy frame of a primitive jerry-built merry-go-round for the church fete. Lofty held up one end easily while my father, brother and I groaned and strained at the other end.

It was important Lofty’s strengths were directed in the right way.

I was reminded of Lofty when reading “The Second Convict Age”, an exposition by Andrew Leigh of imprisonment in Australia.

Leigh is the Federal Member for Fenner, and has one of the best policy brains in the Labor Party and is a former economics professor at the ANU, but that did not stop the party allowing its factional heavyweights to bump him out of the shadow ministry. Merit did not come in to it.

But presumably it gave Leigh time to write “The Second Convict Age”.

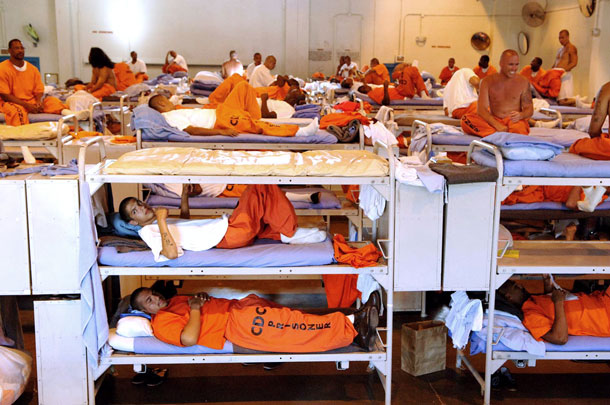

Leigh points out that Australia’s convict population is ballooning with no appreciable advantage and a lot of cost.

Even taking into account population growth, it is has more than doubled since 1985, from 96 per 100,000 adults to 221 per 100,000 – the highest rate since the 19 th century.

But it is not as bad as the US, you might say. The US has more than three times the imprisonment of Australia. However, the imprisonment rate of Indigenous Australians is now higher than that of African Americans. It is 13 times the rate of non-indigenous Australians.

Why has the imprisonment rate gone up so much? There are no doubt many factors, but one of those factors is not more crime or more serious crime. To the contrary, crime rates went down in that period in almost all categories.

For example, the homicide rate has halved in the two decades to 2018, yet the imprisonment rate has doubled.

It does not make sense.

However, my guess is that, if polled, most people would say, contrary to reality, that crime is rising and jail sentences are too lenient.

In Canada, in a similar environment of falling crime, the incarceration rate has also fallen. The sky has not fallen in in Canada and they have probably saved themselves a lot money.

In Australia we are putting people in jail more often and leaving them there longer not for any rational reason associated with sensible administration of justice.

Similarly, the astonishing rise the incarceration rate in the US between 1970 (220 per 100,000 adults) to more than 1000 in 100,000 in 2010 had nothing to do with dealing with a surge of crime or some new research suggesting this would improve society.

In Australia, as Leigh points out, a dominant factor seems to be longer sentences, or at least longer time spent in jail. The average age of prisoners over the three decades rose by seven years, from 29 to 36.

Other factors include a greater propensity to report crime, particularly assault; police taking people to court rather than cautioning; mandatory sentencing; more women and Indigenous people incarcerated; and new laws such as one-punch laws, knife possession, bushfire arson, and cyber crimes.

In all, though, Australia is following some of the unfortunate US trends of between 1970 and 2010 – populism and hysteria stirred on by both traditional media and social media combined with policy-makers promoting privately run prisons.

Our imprisonment rates have more than doubled, which is bad enough. We must not fall into the US trap of sending our rate up five-fold. We have to resist and reverse the trend.

I suspect that social media is having a perverse effect. As soon as a prisoner who committed an horrendous crime two decades or more ago seeks release, all the gory details of the crime are republished as if they had happened yesterday.

Then people get on social media attacking any release or parole. Politicians then respond by passing more laws to make parole more difficult or to impose mandatory sentences, such as “life without possibility of parole” which is so often imposed in the US.

This groundswell then creates a subtle pressure on parole boards and judges who should act independently. But we know they are influenced, on two grounds. First, the incarceration rate has gone up. Secondly, “community standards” are an element in sentencing.

The real problem here, though, is that prisoners are being made to serve a greater portion of their head sentence than they did a few decades ago. But the evidence suggests that the great bulk of crime is done by people in their teens and 20s. Once people, get into their 40s and 50s, they are much less likely to commit crimes and are more suitable for release.

Yes there are risks, but they have to be balanced against cost. Otherwise our jails will become old people’s homes. We need to concentrate more on rehabilitation and education in jail and more on policing because the certainty of being caught is a far greater deterrent than length of sentence.

Even the Americans are beginning to see the absurdity of “life without possibility of parole” – someone in their 90s shuffling about in a jail. The US incarceration rate has been falling in the past decade. We should not go there in the first place.

The full report can be seen here: http://www.andrewleigh.org/PDF/SecondConvictAge.pdf

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 7 September 2019.

CRISPIN HULL

I have been nodding in furious agreement while reading your article Crispin.

We (especially politicians) need to ask ourselves: what is the reason we incarcerate people? Deprivation of freedom is an effective punishment for serious offenders while also giving protection to the public. Some of these offenders may never be released, not just because their crimes were so horrific but because they may always remain at risk of re-offending.

Politicians can also score easy points by appearing to be tougher and tougher on crime.

But what is the point of giving more minor offenders longer and longer custodial sentences? What use is it to anybody? Prisoners are consumed with fear or boredom or both and are nearly always influenced by tougher, older and more hardened prisoners remaining a risk to society. How can rehabilitation happen?

Surely incarceration also needs to offer offenders hope? Hope for a better life.

Psychological and spiritual guidance to help them examine their motives and feelings, enable them to better handle their emotions and make more mature decisions.

Vocational training if they need to acquire skills that lead to employment.

Meaningful work while incarcerated that contributes to the broader community.

Prisons that do not mix hardened criminals with young, impressionable first offenders.

Work opportunities upon release.

And what is the point of prisoners staying so long in gaol that they become institutionalised and incapable of functioning in the community? The social cost/benefit case simply can’t be made. Even the economic cost/benefit case doesn’t add up. We are spending a fortune to pay private companies whose only incentive is to make more money by handling more prisoners.

Is our system of incarceration yet another example of our growing political mean-spiritedness?