Life for a minority Labor Government after the election would be far easier than life for a minority Liberal Government, for one reason: the Senate and how it is elected.

Even if Labor loses a percentage point or two of the overall vote at the next election, it is very unlikely to lose any Senate seats, indeed it could pick one up.

Whereas, even if the Coalition increases its 2022 share of the vote it is still very likely to lose as many as four Senate seats. I will explain the (rather intricate and boring) arithmetic later.

In any event, the position in the Senate will be a factor as to which major party the independents and minor parties might support in a hung Parliament.

It is possible, even likely, that after the election which includes an election for half the Senate, the Senate will split into approximate thirds: a third for Labor; a third for the Coalition; and a third for the minors and independents.

In those circumstances, a minority Coalition is more likely to have its legislation blocked than a Labor one. This is because the great majority of the minors and independents are more to the left or environmentally and socially concerned and because the Coalition is generally less likely to compromise.

This then puts a constitutional shotgun in the hands of a minority Coalition Government. It would argue that its agenda was being blocked by a rabble of independent and minor-party senators and that the minority position in the House of Representatives was unstable, so the air should be cleared with a double dissolution at which the Coalition would argue that stable government could only be returned with majority Coalition government and more Coalition senators.

Once the constitutional shotgun had been handed to the Coalition, the minor parties and independents would very quickly be vulnerable to being forced to another election carrying all the blame for instability.

It is a reason that minor parties and independents should be wary of supporting a Coalition minority Government. A minority Labor government, on the other hand, would be more likely to get its legislation through, and even if it did not, would be less likely to use the double dissolution trigger.

A minority Coalition Prime Minister would never voluntarily agree to a hand over of power to Labor rather than have a double dissolution.

The situation would give the unelected Governor-General, Sam Mostyn, a key position. Does she follow the advice of the Prime Minister almost automatically, even that of the Prime Minister is a minority one? Or does she consult more broadly – say by asking the Leader of the Opposition whether he or she could get a majority on the floor of the House and get Supply through the Senate?

The lack of constitutional clarity about minority government and requests for double dissolutions is a worry. Expect a raging partisan debate.

Now to the arithmetic. Only half the Senate gets elected every three years because senators have six-year terms, not three-year terms, like the House of Representatives.

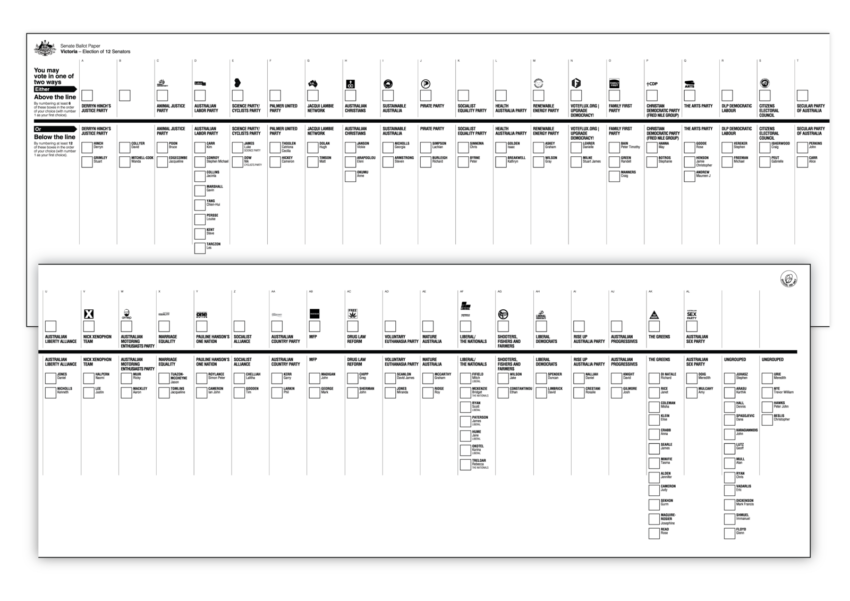

It means that the 36 senators up for re-election in the six states (six senators in each state) were elected in 2019 – you know, the “miracle election” when the Coalition did pretty well. Indeed, the Coalition did so well then that it got three senators elected in four of the states – Queensland, WA, SA, and Victoria.

Given the haircuts the voters have given the major parties since then, it is extremely unlikely that the Coalition can repeat that performance. A candidate needs 14.3 per cent of vote to get a senate seat. To get three in any state the Coalition would need 42.9 per cent of the primary vote.

Polling suggests it has no hope in any state but Queensland where it has a slight hope. Labor got only one seat in Queensland in 2019 so might pick up one more if it gets just 28.6 of the primary vote.

Taking into account the senators who were elected in 2022, a quite likely result of the election of the new state senators in 2025 would therefore be: 24 Coaltion; 24 Labor; and 24 others. You then add the territory senators – at present two Labor; one Coaltion; and one Independent, and likely to stay the same – and you would get a total Senate of: 26 Labor; 25 Coalition; and 27 others.

The ”others” would be the largest block in the Senate for the first time since the two-party system bedded down before World War II.

Over two elections, the Coalition faces the prospect of going from having 36 senators to just 25.

The prospect of either party ever again having a majority in the Senate looks so thin as to be unseeable.

The other consequence is that the two major parties are likely to conspire to game the system to improve their numbers against the minor parties and independents.

There’s a bit of a history of this. In 1983, the major parties agreed to a big Senate numbers move that backfired on them badly.

In 1983 the Senate was expanded by increasing the number of senators in each state from 10 to 12, with six elected every half Senate election. The major parties reasoned that getting three from six (requiring 43 per cent of the vote) was easier than getting three from five (50 per cent of the vote).

They thought – quite delusionally – that they would get 43 per cent each and wipe the minors and independents minors out. It didn’t happen. Virtually all the time the minors and independents got at least one senator in each state and quite often two.

Since 1983, the Coalition has only had a fleeting moment with a majority in the Senate and Labor never.

Do not be surprised if the major parties decide to collude to increase the size of the Parliament so there are 14 senators for each state with seven at each half Senate election. The quota for three out of seven would be 37.5 of the primary vote – well within the range of major-party optimism.

It would dash forever any hope of a major-part majority in the Senate, but that hope is already fanciful. The majors might well conclude that the possibility of squeezing the minors and independents down to just one or two senators out of seven in each state at half Senate elections is a better proposition than the likely post-2025 position of them having about a third of Senate for the foreseeable future.

But as in 1983 it could easily backfire.

Crispin Hull

This article was first appeared in The Canberra Times and other Australian media on 18 March 2025.

Dear Crispin

Thank you so much for your great and enlightening article on the Senate numbers and how the increase to 12 for each state came about. The gaming by the major parties is very disappointing.

Keep up the good work.

All the best,

Teresa

I’m confused by your writing that “well within the range of major-party optimism” on the one hand and “it would dash forever any hope of major-party majority” in the next paragraph. It seems contradictory. There seem to be a few double-negatives there somewhere.

Tasmanian State parties did the same as your 1983 Senate example in the mid 1990s under their Hare Clarke system. In their case they reduced 7 elected representatives per electorate to 5 to raise the percentage required and remove the Greens. The Green vote, similar to current Federal independents, continued to grow and still threaten the balance (a Labor-Green accord is impossible). The majors ended with less talent to even hold necessary Ministerial portfolios and without a backbench. Numbers were increased more recently but the talent pool remains similar to a local council with poor state level required decisions. An unaffordable AFL stadium, collapsing health system, and a lack of salmon farm regulations being the most recent.